In the wake of Charlottesville’s violent rally of white supremacists protesting the planned removal of the statue of Confederate General, Robert E. Lee, artist Edgar Arceneaux contemplates why certain historical pasts return and insist themselves upon the present in his experimental play, Until, Until, Until.

The play is a two-part reenactment of Ben Vereen’s performance in homage to vaudevillian great, Bert Williams, at Ronald Reagan’s inaugural gala in 1981. In the first act, Vereen performed a minstrel show standard—Waiting for the Robert E. Lee, dressed as Williams and in blackface, as it was required of Williams and Black performers of that time. For the second half, Vereen interacts with an imaginary bartender and offers to buy the audience celebratory drinks, only to be refused because of the color of his skin. He closes the number, wiping the paint off his face while singing William’s acclaimed song, Nobody—I ain’t never done nothin’ to nobody, no time.

His critique on the social injustices in America was never aired. Instead, ABC broadcast cut to Donny and Marie performing Stevie Wonder’s For Once in My Life. America only saw Vereen perform a razzle-dazzle number in front of 25,000 mostly white republicans. This stunted Vereen’s career for many years and took a psychological toll on him. Until, Until Until is Ben Vereen’s performance in its entirety. “We are telling the story not only in its historical perspective, but to tell the story in the perspective of how Ben Vereen remembers it, which is as a series of traumas,” says Arceneaux. How are these narrative histories addressed and why are they here now? The play turns to the audience for answers.

Ticket holders entered through the back door of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects gallery, which lead directly to the bar where actor Frank Lawson who plays Ben Vereen served drinks to the audience. “Taking people through the back was a way to connect people to the idea before they knew what the end of the play was going to be about – not being allowed to drink in the front, not being allowed to enter through the front. It’s what’s being set up. I particularly like stories and experiences that rewrite everything you thought you knew,” says Arceneaux. Unbeknownst to the viewers, the play starts there. The audience commingled around the bar and in the room across it with an installation of books.

False Equivalencies—an installation of law books covered in sugar crystals are propped on pedestals like relics of the past. They become a collection of antiquated objects that speculate the wavering nature of social and cultural narratives. Although destructive in appearance, Arceneaux adds that sugar crystals grow organically like the root of a tree; even when dry it absorbs the moisture in the air, like a metaphorical breathing. The crystallization transcends its original function in an effort to provoke and diverge the structure and transmission of information. Theses texts were set up in juxtaposition to a cluster of framed newspaper clippings from the 1960s and 70s of race riots that took place across the country. As the lights dimmed, a gauzy white curtain pulled to reveal a quote by Ben Vereen—“I thought that it went well. Everyone was congratulating me when I left the stage. Two days later my conductor said to me, brace yourself…” silkscreened in a silent movie era typeface. Footsteps were heard from behind the curtain.

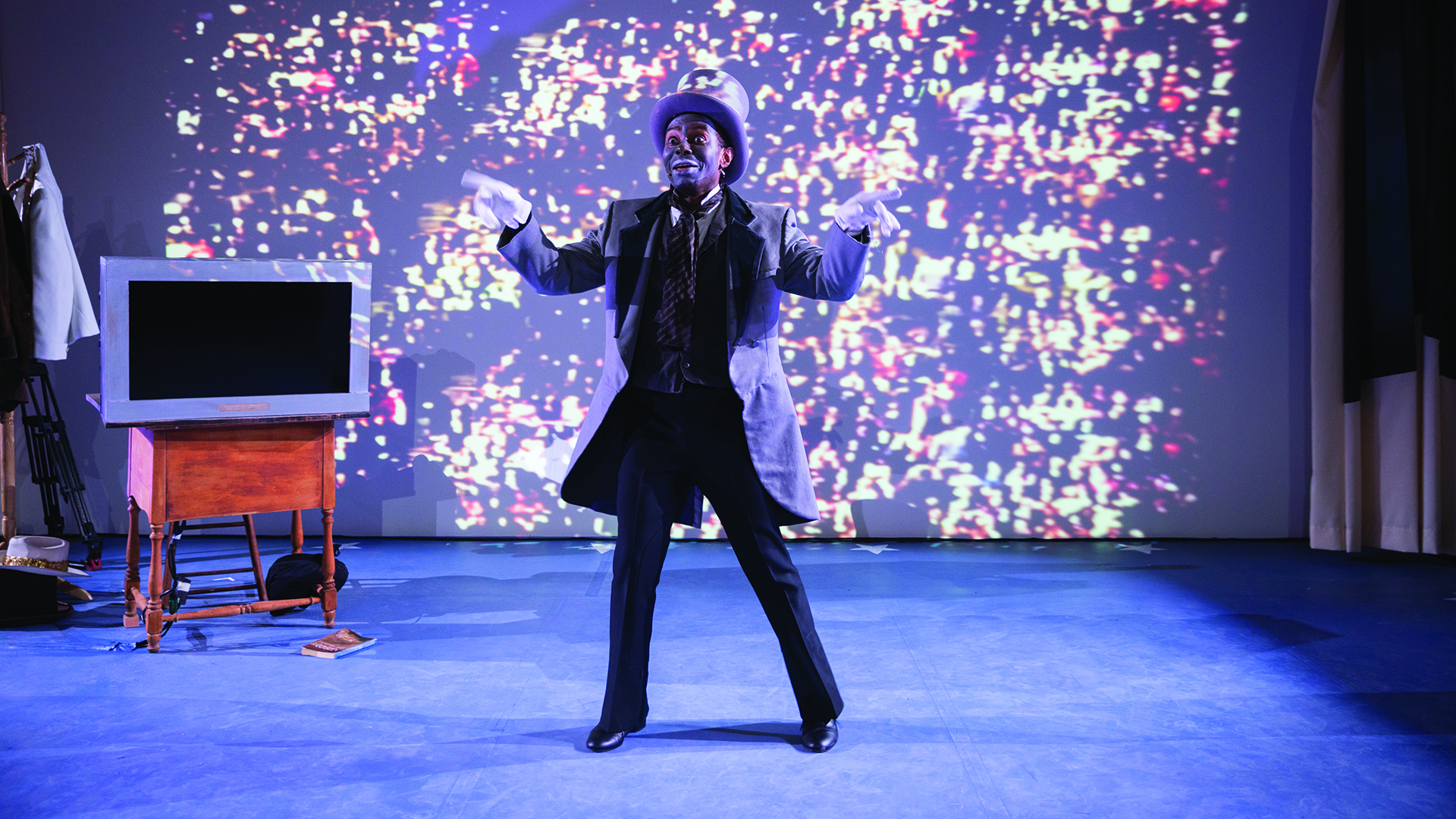

The curtains opened to Frank Lawson, who played Vereen, rehearsing his performance for the inaugural gala behind a clothing rack, make-up table, mirror and cameramen. A few minutes into the play, Arceneaux, who played himself, director and choreographer is heard off-stage asking the actor “How you doing, Ben?” Instead of forcing an abrupt suspension of disbelief, this prologue blurs the start time of the play and generates a sense that the performance started before this. This indistinction creates a precarious feeling among audience members and hints to implication.

The first act continues with another rehearsal of the performance, this time with music. It repeats itself again for the third time. Each repetition has a slight variation from the other. “Its another way of playing with this idea of the return, why is it here now?” says Areceneaux. The audience then watches Arceneaux watch Vereen watching himself on a monitor play a song done almost a hundred years ago. The live footage on the monitor gradually becomes distorted. Vereen’s feelings of defeat and burden slowly approach the viewers’ psyche. The scene was taken from a meeting Arceneaux had with Vereen while the play was in it’s initial stages “I just saw this line between the archetypal past and the transient present” says Arceneaux reflecting on his experience.

Until, Until, Until concludes with the segment that was never aired. Original audience footage from the gala is projected on the walls as the audience is invited to take a seat on stage. Cameras focused on viewers when Frank Lawson delivered his aching reenactment of Vereen’s final scene. The room filled with an unsettling tension and contemplative silence as the play directed it’s gaze to the audience in an attempt challenge our role as a spectator and to re/consider everything that you thought you knew.

The play will tour throughout the country, with a specific intent to perform in battleground and red states. Arceneaux’s documentation of the audiences across the states depicts a clearer portrait of America.